Crozet Gazette Article – The Secrets of the Blue Ridge

by Phil James

Why has Free Union, Virginia, so captured the attention of historians and writers through the years? Perhaps because this rural crossroads town embodies certain gentleness; the architecture along its principal travel routes harkens to the pleasant memories of an earlier time.

Most of the rolling acres in the area had already been claimed when, in the mid-eighteenth century, redrawing county lines put the Free Union area within the new county of Albemarle instead of Louisa. The culture of tobacco planters and their enslaved workforce set the tone in those early years. By Revolutionary times, travelers passing through this region on the Buck Mountain Road could find respite at Michie’s Ordinary two miles east of Free Union. There, a meal and ardent spirits could be had and a bed might be procured for overnight.

In early days, the Buck Mountain Road was a string of roads that stretched from Rockfish Gap, meandered along the eastern base of the Blue Ridge Mountains, passed through Earlysville and ended near Stony Point on the Barboursville road; it became this countryside’s defining thoroughfare. The Mechums and Moormans Rivers conjoin near Free Union and form the South Fork Rivanna River that once carried the commercial hopes of the surrounding region southeastward toward the James River at Columbia.

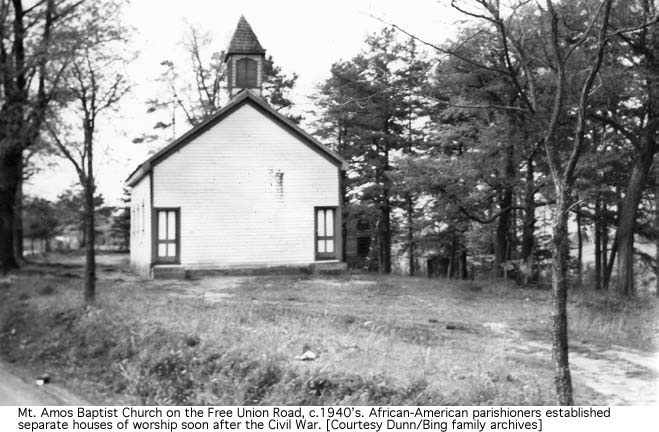

Free Union Baptist Church was established in 1833, and, in 1837, the congregation partnered with Episcopal, Methodist and Presbyterian groups to acquire land with a house for worship, agreeing to share the “meeting house” for their respective religious services. The Baptists eventually became sole possessors of the church building as the other three denominations established individual church sites. The Church of the Brethren started a preaching point in Free Union in 1885.

Free Union was originally known as Nicksville, being identified by the name of the African- American blacksmith who had established his workshop near the village’s eventual commercial center. When the growing population needed a post office in 1847, they adopted the name of the local church to avoid confusion with another similarly-named county post office.

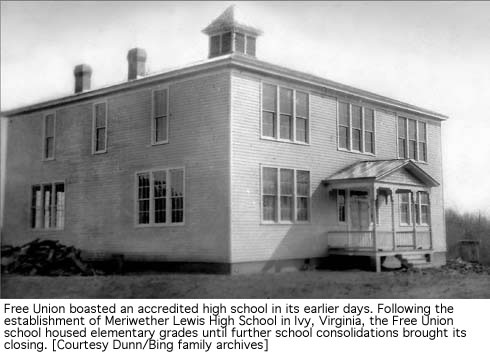

Vera Viola Via (1914–1964), eminent Albemarle County historian and much-beloved daughter of Free Union, recorded the oral tradition that, following the Civil War, the Free Union meeting house was used as a school for the elementary education of African-American children. James Ferguson, a surveyor by occupation, taught eleven students at what was perhaps the first school of its sort in Albemarle County.

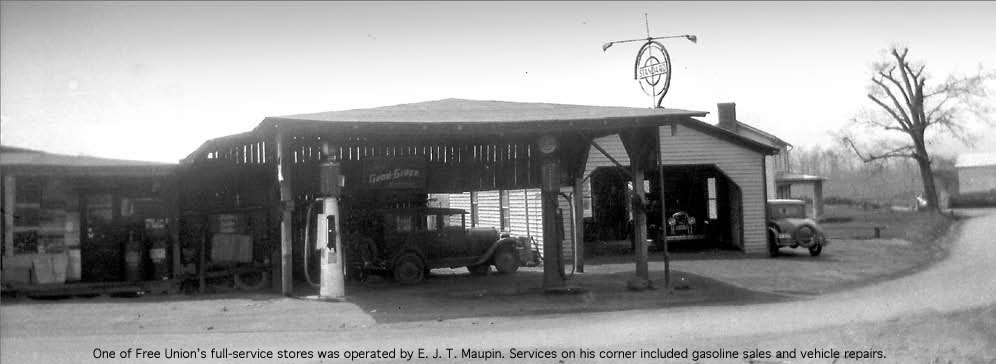

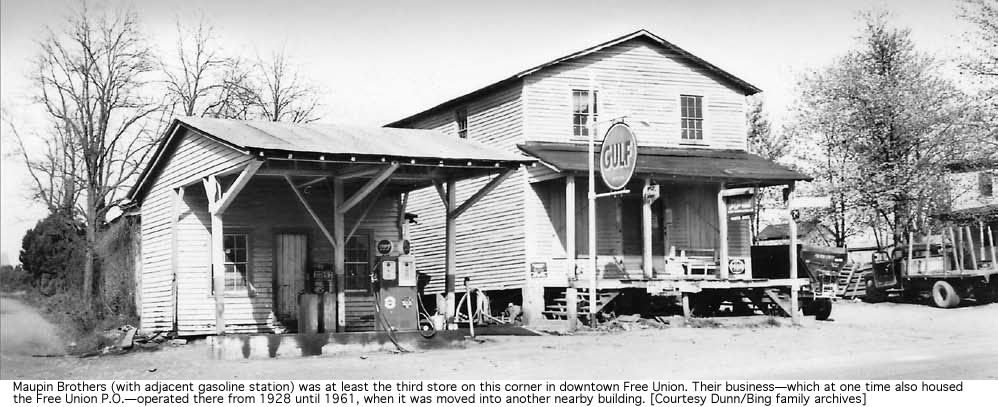

Gradual improvements in roads and bridges encouraged the earliest growth patterns. Teamsters hauled the colonial commodities of tobacco and grains to commercial markets. Blacksmiths and wheelwrights quickly found their services needed, as did cabinet and furniture makers, as the local planters prospered. Water-powered mills eventually gave way to gasoline-fueled engines that ground the grains for local bread, animal feed, and commercial export.

General mercantiles appeared, and competition among them provided choice and convenience, contributing to and further inducing growth in and around Free Union. This pattern remained intact throughout rural America until after World War Two. Then, easier travel combined with greater urban labor needs began to pull workers from the countrysides. By the early 1950’s industrial opportunities in Charlottesville, Earlysville and Crozet changed forever the face and pace of rural life and greatly impacted the commercial centers in small villages like Free Union.

In 1941 Free Union was honored by its selection as the location of the first county-sponsored 4–H youth camp in the state. 4–H Camp Albemarle (not to be confused with the former Civilian Conservation Corps camp of the same name located in White Hall) was sponsored by the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors. Funding and labor were provided by the depression- era relief program Work Projects Administration, along with a donation from the Albemarle Terracing Association, a group that encouraged soil erosion control and soil conservation. The rustic campground and lodge were built in a hollow alongside the Moormans River. Although a number of upgrades have been made to the facility over the years, 67 years of happy campers coupled with hit-and-run vandalism have elevated the need for more regular maintenance and on-premises security. “The Campaign for Camp Albemarle” has been established to raise funds to meet these immediate needs and position the camp for many more years of service to youth.

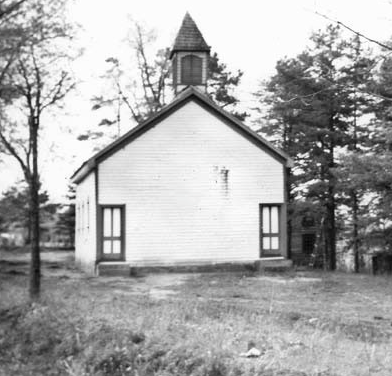

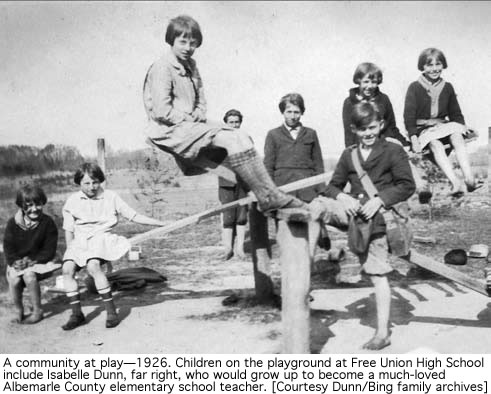

The late Sarah T. Dunn, a Free Union native, along with her sister and fellow school teacher Isabelle Dunn Bing, maintained a keen interest in the early families of the Free Union area. The sisters’ shared hobbies also included the documentation of many of the older buildings around Free Union. (Several of the scenes accompanying this article were photographed by these community minded women).

Among the items kept by Sarah Dunn was this poem:

What Is A Good Community?

Is it people working together regardless of any strife or weather?

Is it homes where privacy is assured and families’ happiness can be secured?

Is it schools where children grow and democracy they learn to know?

Is it factories working night and day to speed production on its way?

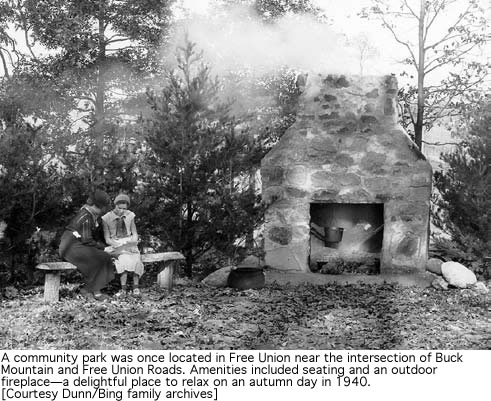

Is it parks that are places of beauty and rest with children’s playgrounds of the best?

Is it highways leading in and out to carry people and products about?

Is it different churches where you pray and serve your God in your own way?

Is it government that listens to you and does what the majority wants it to?

Is it a place where music and art flourish and the minds of men ever shall it nourish?

Is it housing of the best for all and there are no slums large or small?

It is all these things put together which will make a community go on forever.Sarah and Belle read their own hopes for their community in the lines of this poem. As communities throughout the region prepare themselves for inevitable change, the current stewards of Free Union strive—as did their predecessors— to maintain the gentle demeanor of their fair village.

Phil James invites contact from those who would share recollections and old photographs of life along the Blue Ridge Mountains of Albemarle County, Virginia. You may respond to him at: P.O. Box 88, White Hall, VA 22987 or philjames@firstva.com. Secrets of the Blue Ridge © 2008 Phil James

A special thanks to the Crozet Gazette for this excellent article. You should check out their Newspaper in print and online.