Losing Ground

Cville Weekly Article

LOSING GROUND

"It's gone from cows to horses." That's how Kate Steers, longtime resident of Free Union, describes the growth in her area. "It's a telling point," says Steers, "because people who own cows wouldn't own horses. "In other words, things around here have gotten very upscale."

By Kathryn E. Goodson

feature@c-ville.comFree Union is but one of several Albemarle hamlets facing off against the forces of change and growth. To the east, within the loose confines of Earlysville, which is by far the hardest hit of Albemarle's rural villages by new developments and population growth, modern housing tracts seamlessly abut rustic clapboard farmhouses. Its countryside is now dotted with planned gated developments such as Walnut Hill on Earlysville Road, where gazebos line loftily named streets such as Paradise Lane, English Walnut and Grove Park.

In White Hall, 12 miles northwest of Charlottesville, aspiring vintners have moved in from around the country in search of reddish brown Cecil clay, 800-foot elevations and airy mountain vistas. More than the coming year's crop however, these newcomers worry about the development that will be green-lighted later this month when the Crozet Master Plan final report is presented to the Planning Commission and Board of County Supervisors. As Crozet, just south of White Hall, becomes the landing point for Albemarle's "managed" growth, many in White Hall, and other small villages, fear that the County's rural outposts will yield with politicians' blessings to a suburban lifestyle.

And they may find little comfort in County officials' weak reassurances that ticky-tacky suburban development can be avoided. "We are trying to reverse the trend of suburban developments that this nation has grown so accustomed to," says Susan Thomas, senior planner of the Department of Planning and Community Development. Yet most agree that developers, with their homogenous visions for housing and community, continue to have their way in Albemarle.

Covesville, located in the southwest portion of the County, was once an agricultural boomtown. But in the early 1960s, Covesville took a hit from which it never quite recovered: A four-lane highway was paved directly through its middle. Today un-walkable, un-crossable Route 29S shears the small town in half.

Throughout Albemarle, pockets of seemingly unregulated growth have taken their toll on many once pastoral areas.

Somehow, these places hold on to a sense of community, it has not been among growth's casualties. Some of Albemarle's villages might no longer have post offices, but they retain unofficial town mayors, ice cream socials and informal parades. Ruritan clubs hold court on a monthly basis, and community clean-up days are a normal occurrence. Some might say these small outposts put larger communities like Charlottesville to shame.

Only 17 miles southwest from Charlottesville, the historic village of Batesville is a prime example. The words "spirited" and "charming" spring immediately to mind when describing this place designated by the National Register of Historic Places. A look at the changing faces of Batesville, Covesville, Free Union, White Hall and Earlysville follows.

Batesville

Its center of gravity might soon shift, yet ice cream socials, and public hearings, endure

In 1998, John Pollock, unofficial mayor of Batesville and official president of the Batesville Historical Society, posted 50 signs alongside the village's main street, Plank Road. Their message: "25 MPH, please." The following morning, 47 of the 50 signs were missing, wooden posts and all. Adding insult to injury, most of them were found floating in the water nearby.

Four years later, Pollock finds himself center stage again in the battle against development and its byproducts.

"What I'm most afraid of is major traffic on our Plank Road," he says. "I mean, look what happened to Covesville."

Although Batesville's Plank Road is certainly no Route 29S, it is a thoroughfare for traffic to Scottsville.

Yet internal growth pressures jeopardize Batesville as surely as does southbound traffic to Scottsville. Last December, for instance, Jess Haden, lifelong resident of Batesville, went before the Albemarle County Planning Commission requesting preliminary approval to create 11 lots under a rural preservation development. Batesville residents turned out for the meeting in droves. It was not the first time locals aired their distaste of upcoming development.

Pollock spoke to the Board about the proposed development's proximity to Batesville's historic district, noting that the local historical society feels that they "have to acts as stewards of this district to protect it."

Ross Weesner, member of the Friends of Batesville group, also stood before the Board at that time, pointing out that he'd moved to the rural Batesville area specifically so he could raise his family away from mass development.

To date Haden has done nothing with his land, but victory against change is by no means complete. Batesville has another issue that separates it from villages such as White Hall, Free Union, Covesville and Earlysville: It stands to lose the unofficial town meeting place, Page's Store. In this case, the threat arises from something less sinister than uncontrolled growth, namely the desire of the younger generation to move out of the family business. There's nothing wrong with that in itself, of course, but the County's ancient Rural Area zoning laws hold that if a store discontinues its commercial uses for an extended period it can revert to residential zoning. In Batesville, in other words, a private residence could replace the keystone holding "downtown" in place, and likely it will be inhabited by a pastoral-seeking outsider.

"If these rural stores remain unused, they fall into disrepair," says Susan Thomas, senior planner in the County's Department of Planning and Community Development. "We're hoping to be able to allow for some potential for these old structures." Indeed, Thomas' office is reviewing rural zoning laws. In the meantime, Page's Store, one of 42 nationally designated historical buildings in Batesville, is facing a one-year deadline to restore to commercial use, unless the zoning laws are changed before next July.

Community is anything but an abstract notion for residents of the place once known as Mount Israel, named for Solomon Israel, who purchased 20 acres of land near Stockton's Thoroughfare in 1764. Today's Batesville community is centered around ice cream socials, Batesville Day celebrations and apple butter festivals. And, the evidence shows, public meetings.

"We are not afraid of going in front of the County and expressing our wishes about not too much growth, that's for sure," says April Freeman, head of the Batesville Day Parade.

Covesville

With its population halved after Route 29S cut through town, new residents try to halt a road to ruin

Sarah Dollard closes the lid to a mini Weber grill. The waft of well-done hamburgers and dust hangs in the humid June air. From the broad unfinished porch of the 9,500 square-foot Covesville Store, of which she is the new owner, the faint sound of traffic on Route 29S is concealed intermittently by a distant rooster. A band of trucks from the State Department of Transportation paints lines on the freshly re-paved road.

Dollard and her partner, Rick Ovenshire, purchased the vacant yellow building alongside 29S last December, moving into the second-floor residence above the store in January. Their acre includes the post office and the remains of an old vinegar press. In Covesville, this adds up to "downtown." As newcomers to a centuries-old village, Dollard and Ovenshire tread lightly.

"We consider ourselves moderates," says Ovenshire. "We like both the old-timers and the newcomers." For the most part, longtime locals seem to have taken to the new country store-owners. At least once a day a different passerby drops in to request that when the store opens for business within the coming month it stock beer, comestibles and toilet paper.

Not that Ovenshire and Dollard have avoided "old timer" run-ins, there were some who complained when recently they began filling in the vinegar press for a parking lot.

"We were afraid someone was going to fall in," explains Dollard. "It was a huge hole in the ground."

Such can be the fate of once important landmarks.

At a time when Covesville was little more than a dirt road, lolling apple orchards and productive farms flanked by crooked wooden fences, the Covesville Store (then called Purvis and Johnson) was one of four retail places in town. The village boasted a population of more than 1,000, and the area was known for its "Albemarle Pippin" apples, shipped frequently to England.

The first blow to the village was a non-poisonous but foreboding scab that appeared on apples being exported, leading England to cancel its orders in the late 1920s. The second blow landed in the 1960s, when VDOT sealed Covesville's fate with the paving and widening of Route 29S. Farm workers left for greener pastures, and the population was nearly halved.

With the shops reduced nowadays to only one, the Covesville Store carries the full load of local history. Indeed, back when it was known as the Purvis and Johnson Store, it was the only interracial shop in town.

Behind the edge of the porch are other remnants of a once lively retail history, including a gray cinderblock smokehouse.

"This is where North Carolina pigs became famous smoked Virginia hams," Dollard says. Although Dollard and Ovenshire don't plan to smoke anything, they do plan to sell antiques, imported jewelry, groceries and local wines. The two also run an online jewelry and antiques business. Like other young professionals who return to the land, Dollard and Ovenshire are trying a decidedly modern recipe for ex-urban living, cyberspace meets rustica.

"We want this acre to cross all boundaries of race, age, religion and socio-economic background," says Ovenshire, who nonetheless, and perhaps realistically, expects that most of the couple's income likely will come from Internet retail. "There's a lot of foot traffic that we think will be coming to the store, and as for the jewelry and antiques, this building is the first thing you see when crossing into Albemarle County."

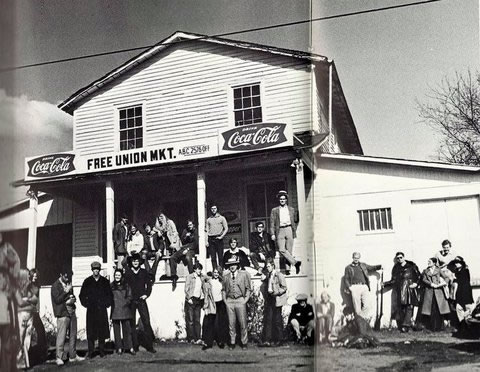

Free Union

What the Civil War couldn't tear apart, yuppies might

Kemper Maupin points to an uneven line of children's handprints forever embedded in the parking lot of the Maupin Brother's Store. Pushing away dirt and loose gravel, he points to his own, impressed in years gone by. The words "Maupin family" are barely visible above the imprints.

Maupin has owned the Maupin Brothers store for more than 75 years, he's seen his fair share of change in the area where he grew up. When asked to describe the change, he sighs and shakes his head.

That's how Keith Huckstep answers the query, too. Huckstep has worked at his father's business, Huckstep's Garage, for more than 30 years. Huckstep squeezes between a car on a jack and piles of used tires unsteadily stacked against the walls of the 78-year-old building, which was once home to a store with a mill out back. Beyond the display windows, the verdant rolling hills and clean skyline command attention.

"There are a lot more cars," he says, stepping on the fender of a Subaru station wagon, listening for a grinding noise. "A lot more."

"And a lot more people," adds Kate Steers, longtime Free Union resident. You hear that a lot, too, from Free Union locals: There are people here now who weren't here before. Many watch as this once quaint village, like its County brethren, evolves into a popular destination for newcomers in search of quiet, countrified living. But as the populations grow, village boundaries become obsolete, absorbing other small areas. Old-timers subscribe to the sad notion that in another decade Albemarle County will be nothing but sprawling subdivisions crowded with insta-houses on increasingly smaller plots of land.

"Albemarle is a traditional County, but with all the new families coming in, it makes it tough for the families that have been here for a long time," says Eric Strucko, Chairman of the County's Development Initiative Steering Committee and a Free Union resident. "The dynamics have changed."

For instance, when Steers moved to the area in 1978, she lived in the Faith Mission Home village on the border of Albemarle and Green counties. It had its own store and post office. That was then. Nowadays, her postal address is Free Union.

"Mission Home just plain disappeared," she says.

"This used to be a place where old hippies could buy a piece of land and enjoy it," she adds. "Now, the price of land here drives those same people out."

Indeed, those intent on staying put face a rising cost of living and fear of higher taxes as Free Union goes upscale. "I think it's a telling tale that the house I recently moved from," says Steers, "my neighbor just put in a heliostop on his property. Can you imagine? One woman stood at the Board of County Supervisors meeting and actually reasoned that helicopters were a perfectly normal mode of transportation in this day and age."

But what is the battle against up-market growth to a village that survived the Civil War unscathed? Originally dubbed Nicksville after a freed slave blacksmith named Nick, the village changed its name upon acquiring its own post office in 1847, the name "Nicksville" was already claimed by another locale nearby. It became known then as Free Union after its historic church, a multi-racial mix of Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Methodists and Baptists that "freely" welcomed all.

The Free Union Church was the first of its kind in recorded County history to hold classes for black students after the Civil War. As of 1885, the village consisted of 31 families, two distilleries, one corn and flour mill, two local doctors, 21 farmers, two coach and wagon builders, two liquor shops and three general stores, one of which stood on the same site as Maupin's original general store, itself the stuff of legend. (Maupin's original two-storey, three-bay store was across the street from the current location. Two other stores are said to have been located there where Route 601 meets Buck Mountain Road, one destroyed by arson after the notorious murder and decapitation of a 25-year-old store clerk named Thomas Thompson, for which Free Union resident Taylor Harman was charged, convicted and hanged.)

To answer the question, growth is the kind of challenge that can bring out the contradictory impulses in even the most well-meaning residents. Strucko and his family moved to Free Union from the Hydraulic Road area in 1998, to pursue the rural lifestyle that attracted them. "But we weren't going to build new," he recalls.

"What bothers lifelong residents the most is that newcomers move in, contribute to the population growth, and then turn around and preach to stop the growth," says Strucko.

White Hall

Drawn to the vistas, newcomers hope to pull up the drawbridge behind them

In 1988 Tony Champ sold his New York-based chemical company and went in search of the perfect spot for a vineyard. Tony and his wife Edie, upon discovering the consistent breezes and sumptuous views White Hall has to offer, purchased a plot of land there in 1991, preparing to plant six acres of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay and Merlot grapes the following year.

Champ acknowledges the hypocrisy in his own view of growth now that he's not as much of a newcomer: Close the door to new development.

"We moved here as newcomers," says Champ, "and right away we didn't want to see any growth.

"I guess, in that way, I am part of the problem."

His story is not unique. In Covesville, Free Union, Batesville and Earlysville, too, like White Hall, newcomers are quick to fight additional development.

By contrast, says Strucko, who chairs the County's Development Initiative Steering Committee, longtime residents are mostly inclined to accept their fate, reluctant to complain about sprawl.

White Hall, 12 miles west of Charlottesville, has gone through a long litany of names, William Maupin's Store, Maupin's Tavern, Shumate's Tavern, Glenn's Store and Miller's Tavern, until in 1835 the Reverend Edgar Woods permanently named the town White Hall. Through most of that transitional nomenclature, the two-storey Wyant's Store, at one time hosting a dance hall upstairs, has been a community fixture, celebrating its 115-year anniversary this year. White Hall's brick-and-columned Mount Moriah Methodist Church was one of the first Methodist churches in Albemarle County. In 1985, an order of the American Trappistine Monastery purchased 507 acres in White Hall, where to this day the sisters of Our Lady of the Angels monastery bend their backs over massive vats of Gouda cheese for their mail order business, Monastery Country Cheese.

Among other things still unchanged in the village of White Hall is interest in preservation of the land, aided by the now popular notion of conservation.

Champ, for instance, recently placed his 300-acre White Hall property into conservation, a step often endorsed in the DISC forums as a way to avoid the further dissipation of open land into housing tracts.

"When we go to Crozet, we are completely shocked," says Champ. "We can turn off onto any road there and we simply cannot believe the growth."

"We think that a lot of the time people respond to what the housing market offers them," says County planner Susan Thomas, "therefore creating demand in a certain area.

"The way to make this work though, is to have more alternatives for people, not simply one or two subdivisions for example, and then remain firm in the rural-area policies," she says.

Still, giving landowners incentive not to develop a plot of land in the County seems only to solve half the problem. Politics and the inviting economics of suburban-style development cannot be held at bay by conservation alone.

The invasion of traffic concerns Champ, whose winery and home are located only 13 miles from the Barracks Road shopping center, as it does Batesville activist John Pollock, whose efforts to slow traffic on the main drag (which can be a shortcut to Scottsville) went awry.

Crozet and Route 29N may be the County's designated growth areas, but try telling that to those who are watching their two-lane country road turn into a thoroughfare. Maybe it's time to recast growth plans, period, meaning it's time for the County to recognize the City for what it is and coordinate development efforts accordingly. That's the view, for instance, of Bill Daggett, an architect and planner who, with his firm Daggett and Grigg, has spent a career researching sustainable growth issues.

"When you're carving up as much land as we're talking about here, certainly we could look to rearrange some of it into the urban fabric already there," Daggett says. "Downtown Charlottesville.

"That's where we should be concentrating larger developments, in the existing infrastructure."

Earlysville

Start your engines. Earlysville Road is the poster child for sprawl

Earlysville has taken the brunt of the development in the County, no doubt about it," says Eric Strucko, chairman of Albemarle's Development Initiative Steering Committee. "Subdivisions have popped up, it is no longer this quaint crossroads community, and people there are somewhat resistant and feel torn." Within the last decade, traffic has mushroomed along the village's curvaceous main route, Earlysville Road, which some call the Earlysville 500.

"No matter the time, nor the day, turning out onto Earlysville Road is a challenge, to say the least," says Earlysville resident Bill Daggett. "There is constant travel on this road."

Daggett is no stranger to development or its prospects, he's been an architect, planner and designer for more than 20 years. His firm, Daggett and Grigg Architects, has long researched sustainable growth, Daggett and Grigg designed and occupied the multi-use Queen Charlotte Square building on High Street in Charlottesville 18 years ago. "Multi-use" is what the DISC plan purports to be all about. Not that Daggett is entirely buying into the DISC rhetoric.

"I don't believe anyone understands the impact of the DISC initiative because it hasn't really been done before," says Daggett. "This whole evolution of developing real estate is incredibly complex and extremely flexible.

"It's impossible to unravel it all and say there's some definitive way for it to be."

During the past three decades, the County's Comprehensive Plan has stated that for areas such as Earlysville, earmarked as a small-scale growth village, "vegetation plays a major role in defining the old village and will play a major role in permitting sympathetic development to occur in both the old and expanded village if adverse effects are to be avoided."

Yet the vegetation of Earlysville village center has been edged in by subdivisions in the classic Americana mode complete with one-acre lots. Don't expect that trend to reverse any time soon, either.

"As concerns the current neighborhood models we speak of, you can talk of putting people in small multiple family developments, but that's not what people want," says Daggett. "They want their own home, on a plot of land, be it big or small.

"You cannot change people, initiatives or not, solely because you want to change them."

Earlysville, in other words, stands as a case study for those who don't want growth in their area as well as for those who acknowledge that it's here to stay.

More than 100 years ago, James Early purchased 1,800 acres of land near Buck Mountain Creek and the strikingly beautiful ring of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In 1883, he granted land near the creek for a non-denominational church, and the clapboard white frame still serves as a landmark from an era when several present-day residences along Earlysville Road were gas stations. Other historical remnants show signs of change these days too.

Matthew Crane and his wife, Suzanne, own Mud Dauber Pottery on Earlysville Road, in the site once known as Wood's Store. Like other transplanted professionals Sarah Dollard and Rick Ovenshire, who took over a general store building in Covesville, the Cranes have restored an aging and venerated village structure into something more modern.

In 1997 they converted the 1,500-square-foot building into a gallery for Suzanne's high-fired stoneware and tiles, also making a home for three potter's wheels and electric and gas kilns. They've restored the former Wood residence on the same property for their own use. Their renovations are shining examples of the sprawl-minimizing growth that Strucko advocates. Nevertheless, the traffic Mud Dauber's customers might add to Earlysville is a concern.

"I worry that a byproduct of too much growth in this area could be the widening of Earlysville Road," says Matthew Crane. "That would certainly affect our business and our home."

©Copyright 2002 Portico Publications